Are you one of the people who make resolutions every January? I confess I am not –I often just carry on with unfinished goals from the previous year. But is the practice of New Year’s resolutions a modern one, with our recognized focus on self-improvement and achievement? Did people in the Regency era take the time to reflect on their past years and did they make resolutions, too? If they did, was their focus the same as ours?

A quick dive into the history of New Year’s resolutions reveals that the practice dates back at least 4,000 years (if not longer, if it may be ascribed to human nature!). The ancient Babylonians, with their agricultural culture, recognized and celebrated the start of each new year when the growing cycle renewed at the spring equinox (circa March 20 on the modern calendar). Their twelve-day celebration, called Akitu, signaled the start of the farming season, a time to crown or renew loyalty to their king, and also the time to promise to pay their debts. One common resolution, according to some sources, was the returning of borrowed farm equipment! Starting the new year “right with others” was believed to insure good fortune for the seasons ahead.

The Romans adopted the same practices, including the making of resolutions, with the same timing until about 46 A.D. when Julius Caesar introduced the Julian calendar. He set the start of the year as January, named after Janus, the forward and backward-facing Roman god of doorways and gates, beginnings and endings, forward planning and backward reflection. Sacrificing to the god and promising to be better people were meant to bring good fortune just like the Babylonian resolutions, but a stronger emphasis on moral character was added by the Romans.

When Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century, religious practices replaced resolutions and anything else associated with the pagan Roman customs. For instance, the Feast of the Circumcision was set to be observed on January 1 with prayers and fasting, rather than the revelry that non-Christians indulged in.

Over the following centuries the changes met with varying success, however. During the Middle Ages, a sort of New Year’s resolution was made by knights who would renew their vow to chivalry by making their annual “Peacock Vow”–placing their hands on a peacock (cooked or not) during the last feast of Christmastide (usually Twelfth Night) and recommitting to the moral and social code of conduct.

According to historian/author Bill Petro, by the 17th century “the Puritans urged their children to skip the revelry and spend their time reflecting on the year past and contemplating the year to come. In this way, they again adopted the old custom of making resolutions. These were enumerated as commitments to employ their talents better, treat their neighbors with charity, and avoid their habitual sins.”

But “New Year’s Resolutions” as an identified thing was still not the common concept it is today.

In the 18th century, making resolutions (other than those creating laws and regulations) was a firmly entrenched practice, especially among the religious. In 1710 we can find the writer William Beveridge, in his treatise “Private Thoughts Upon Religion, Digested into Twelve Articles,” writing: “And how, then, shall I be able, of myself, to resolve upon Rules of Holiness, according to the Word of GOD, or to order my Conversation according to these Resolutions….”

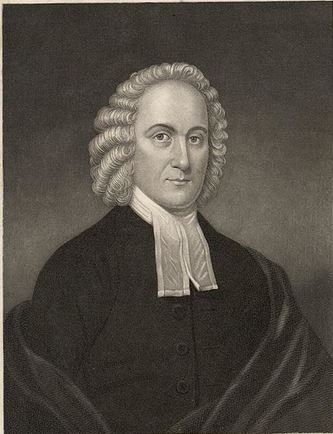

A decade later (1722-23), the young Puritan-raised American theologian-to-be Jonathan Edwards wrote down his resolutions over the course of two years after his graduation from Yale University. He created seventy of them altogether, that he tried to review on a weekly basis. But young Puritans were trained to practice self-examination and introspection, indeed, as were entire congregations.

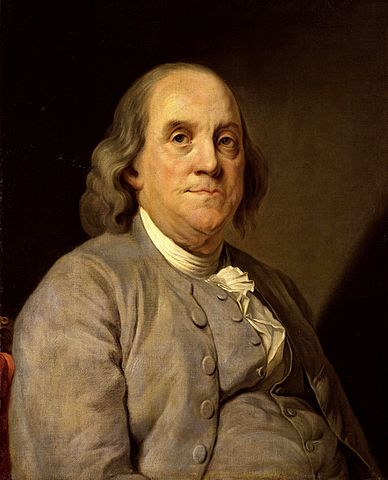

Edwards’s resolutions are often compared to the resolutions penned by another noted American of the period, Benjamin Franklin, whose resolutions (published in his Autobiography) for guiding a good life numbered merely thirteen.

According to George S. Claghorn (Editor, Letters and Personal Writings (WJE Online Vol. 16) ): “Both men agreed on the value of making resolutions, evaluating their effectiveness, and following them lifelong. And the resolutions show that the two were united on the importance of speaking the truth, living in moderation, helping others, and doing one’s duty. Each counseled himself (and others) to avoid sloth, make good use of time, cultivate an even temper, and pray for divine assistance; and each offers an energetic, thoughtful approach to life.” However, as the writer points out, Edwards’s focus was on producing “a soul fit for eternity” and Franklin’s was on producing “a good citizen” of this world.

John Wesley, founder of the Methodist movement, was an 18th century influence on practicing New Year’s resolutions. In 1740 he created a new worship service he called the Covenant Renewal Service, most commonly held on New Year’s Eve or New Year’s Day. It became the root of the “watch services” still held by some evangelical Protestant denominations today, and included praying and making resolutions for the year ahead instead of indulging in revelry.

Apparently, a Boston newspaper from 1813 featured the first recorded use of the phrase “New Year resolution,” although it seems clear the concept itself was already common. The article states:

“And yet, I believe there are multitudes of people, accustomed to receive injunctions of new year resolutions, who will sin all the month of December, with a serious determination of beginning the new year with new resolutions and new behavior, and with the full belief that they shall thus expiate and wipe away all their former faults.”

In fact, one source claims that as early as the 17th century there were jokes about people failing at their intentions to become better in some way in the coming year.

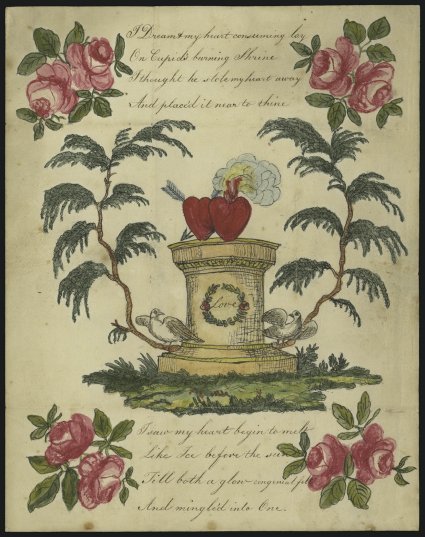

I would say it’s safe to say yes, in the Regency decades people were commonly making (and breaking) New Year’s resolutions, even if they didn’t call them that, for in that time period the “multitudes” of Americans doing so were still generally aping whatever people in the United Kingdom were doing.

Were they making resolutions to lose weight, give up drinking, or get more fit? These “self-improvement” promises are typical of modern times. The top New Year’s resolutions for 2021 were “living healthier 23% of people, getting happy 21%, losing weight 20%, exercising 7%, stopping smoking 5%, reducing drinking 2%. In addition, people resolve to meet career or job goals (16%) and improve their relationships (11%).”

In Regency times, for one thing, most people were more fit and got more exercise in the normal course of everyday life. Their resolutions were much more likely to be outward-looking: about their relationship to others and the world around them, and to have a moral imperative attached: to be more charitable, for instance. If you had lived during the Regency, what do you think your resolutions might have been?