How do you feel about epilogues? Does it seem to anyone else that there’s a “current trend” going on to include them at the end of every story? I think every recent book I’ve picked up lately has had one. Is it a fad, or a change in readers’ tastes and expectations? Or is having that extra glimpse into the characters’ happy-ever-after ending something readers have always wanted all along? Do romances always need to have one?

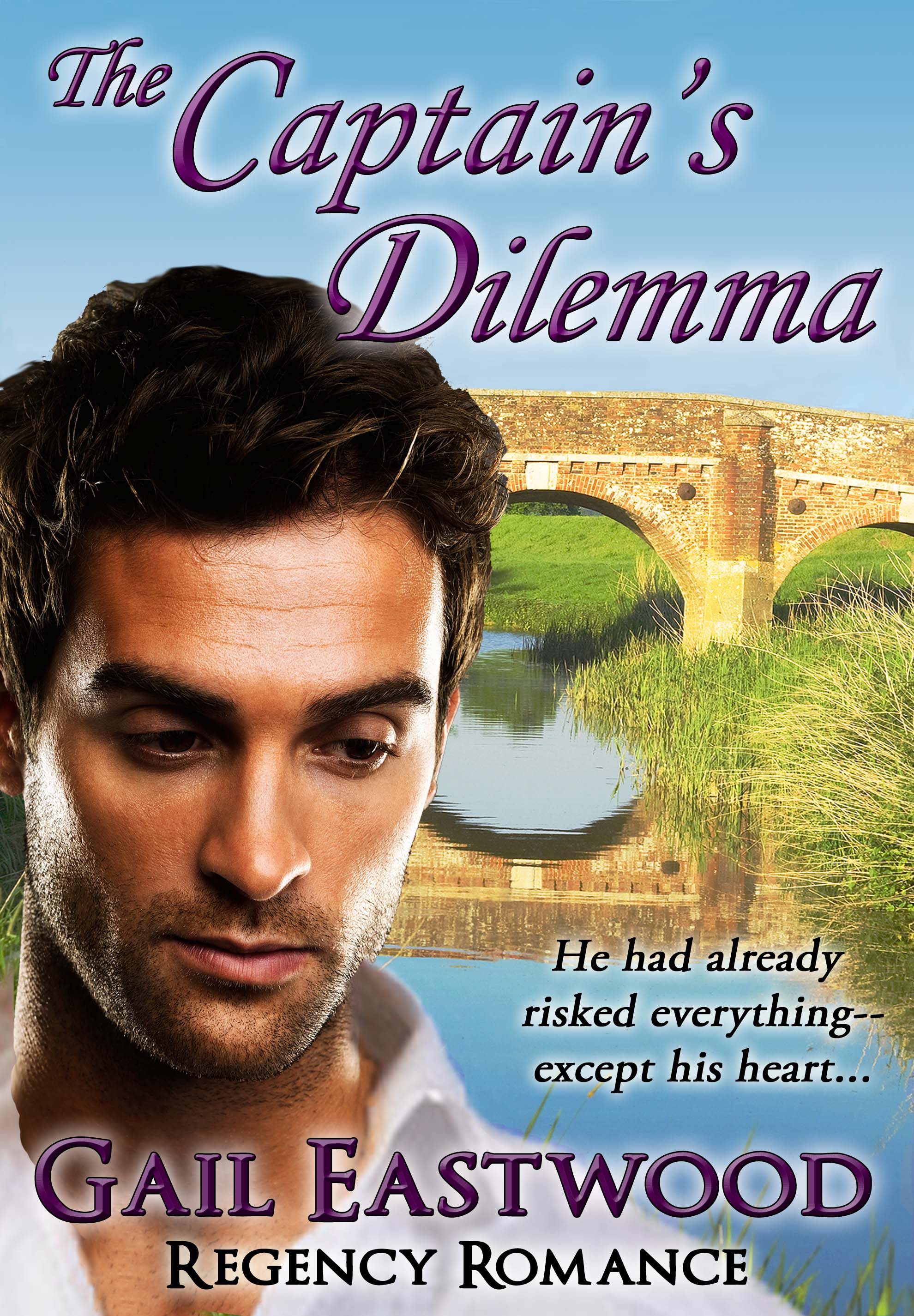

I have been noticing and thinking about this, because I decided to add an epilogue to The Captain’s Dilemma while re-editing that book for reissue. TCD (my third book, published in 1995) is out now, I’m excited to report, on Amazon for Kindle and B&N for Nook, and also for Kobo and other formats through Smashwords. This is my “prisoner-of-war” romance. Read on below for details on the giveaway!

I have been noticing and thinking about this, because I decided to add an epilogue to The Captain’s Dilemma while re-editing that book for reissue. TCD (my third book, published in 1995) is out now, I’m excited to report, on Amazon for Kindle and B&N for Nook, and also for Kobo and other formats through Smashwords. This is my “prisoner-of-war” romance. Read on below for details on the giveaway!

Meanwhile, back to our topic. I used to feel that a good romance that ended properly shouldn’t need an epilogue. If all the obstacles were overcome, the loose ends were tied up, and the hero and heroine finally figured out they were in love, admitted it to each other, and committed to a future together, that certainly seemed very satisfying to me! “Trail off into the sunset” endings were considered bad form.

Yet I think we all enjoy thinking of the characters we come to know and love during a good story as continuing on with lives that last beyond the pages of the book. So the question becomes, do you want the author’s view of it, or would you rather imagine it for yourself? And has this changed over time?

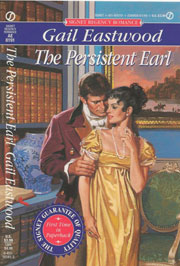

I used to call the lovely but inaccurate Allan Kass cover for my second book, The Persistent Earl, a “visual epilogue”, explaining that it showed the artist’s vision of the hero and heroine together after the story was over. (The heroine, a young widow, wears half-mourning throughout the book, but as you see here, on the cover she is in a beautiful gold satin gown.) Readers always thought that made perfect sense! Can you imagine the rest of this scene without having the words? I consider reading a collaborative process, and even though as an author I give the reader the specifics of my story, each reader brings some of her own imagination into the mix as she reads. I think that’s one of the great pleasures of reading, and one of the (many) reasons movie adaptations of our favorite books don’t always succeed –one director’s view of the story may not match up well with the personal version we have envisioned in our own heads. Ah, but that’s another entire topic.

I used to call the lovely but inaccurate Allan Kass cover for my second book, The Persistent Earl, a “visual epilogue”, explaining that it showed the artist’s vision of the hero and heroine together after the story was over. (The heroine, a young widow, wears half-mourning throughout the book, but as you see here, on the cover she is in a beautiful gold satin gown.) Readers always thought that made perfect sense! Can you imagine the rest of this scene without having the words? I consider reading a collaborative process, and even though as an author I give the reader the specifics of my story, each reader brings some of her own imagination into the mix as she reads. I think that’s one of the great pleasures of reading, and one of the (many) reasons movie adaptations of our favorite books don’t always succeed –one director’s view of the story may not match up well with the personal version we have envisioned in our own heads. Ah, but that’s another entire topic.

My decision to write the Captain’s Dilemma epilogue was fairly easy –I never felt the book quite ended with all the loose ends tied up. More information about how the future was going to work for my French hero and English heroine was needed, but for the old Signet Regencies we had some strict length restrictions, and I had no room to add more back then. It has been great fun revisiting my characters and adding the extra scene they so deserved!

So what do you think? Are we seeing a “trend” for epilogues in romance now? Do you like them? If you are a fan of story epilogues, have you always been one? Is the abundance a recent phenomenon, or have I just become more aware of it lately? I’m going to give away a copy of The Captain’s Dilemma to someone randomly chosen among those who comment, and if we get a lot of comments, I’ll give away a second one! Keeping it simple. Please jump in. I’ll be very interested to hear your thoughts!

And if you want to know more about TCD, you can click here to see it on my web site. Or you can click here to see it on Amazon.

When the opportunity arose to sell my proposal for a Regency-set single title historical,

When the opportunity arose to sell my proposal for a Regency-set single title historical,  The Hospital received its first orphans in 1741. Between 1742 and 1745, the handsome red brick building with stone facings that would serve as its permanent home into the 1920’s was built in Bloomsbury. The hospital continued as an orphanage until the 1950s when public opinion and British law shifted to home-based alternatives to institutionalization.

The Hospital received its first orphans in 1741. Between 1742 and 1745, the handsome red brick building with stone facings that would serve as its permanent home into the 1920’s was built in Bloomsbury. The hospital continued as an orphanage until the 1950s when public opinion and British law shifted to home-based alternatives to institutionalization. Perhaps most moving is the exhibit of foundling tokens–buttons, scraps of cloth and other everyday items–pinned by mothers to their baby’s clothes upon surrender. In the early days, children were baptized and renamed upon admission, so these simple tokens helped ensure correct identification, should a parent ever return to claim their child.

Perhaps most moving is the exhibit of foundling tokens–buttons, scraps of cloth and other everyday items–pinned by mothers to their baby’s clothes upon surrender. In the early days, children were baptized and renamed upon admission, so these simple tokens helped ensure correct identification, should a parent ever return to claim their child.